The Grapevine Art & Soul Salon

Museum

In the last issue of The Grapevine we included an IN MEMORIAM chamber for Ivan Lester, who died in the spring. We are extending Ivan's imaginal life by turning the memorial into a museum where he will be represented in each issue as his own Muse prompts us what to post by or about him or in his interest.

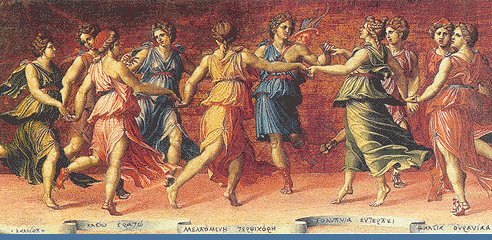

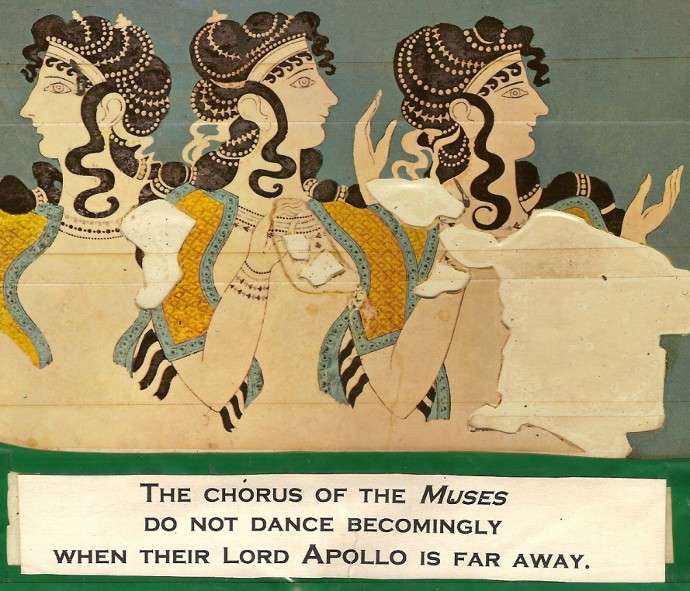

The word museum refers to a "shrine for the muses," an assembly of nine female immortals representing each of the Greek arts. They sang or danced or made poetry under the aegis of Apollo, the god whom Ivan most resembled in his fine mind, his philosophy, his love of beauty and ideal forms (he also loved Apollo's brother Dionysos, the emblem of our website, but that is another story).

Hesiod even gives their [the Mousai] names when he writes: "Kleio, Euterpe, and Thaleia, Melpomene, Terpsikhore and Erato, and Polymnia, Ourania, Kalliope too, of them all the most comely." To each of the Mousai men assign her special aptitude for one of the branches of the liberal arts, such as poetry, song, pantomimic dancing, the round dance with music, the study of the stars, and the other liberal arts." Diodorus Siculus, Library of History 4.7.1

The reader will have noticed that our website logo includes the line: Musings on Being and Becoming Human. What distinguishes us from the gods in Greek thought is our mortality. They wrote much and often about what it means to be human. Sometimes they reflected on mortality through the speech or action of the gods. In the last issue we quoted from one of Ivan's favorite stories. Here is a passage about the death of Achilles, another favorite. The muse Kalliope speaks to the mother of Achilles about her loss, one that we who loved Ivan have suffered as well:

[At the funeral of Akhilleus] To Thetis spake Kalliope, she in whose heart was steadfast wisdom throned: 'From lamentation, Thetis, now forbear, and do not, in the frenzy of thy grief for thy lost son, provoke to wrath the Lord of Gods and men. Lo, even sons of Zeus, the Thunder-king, have perished, overborne by evil fate. Immortal though I be, mine own son Orpheus died, whose magic song drew all the forest-trees to follow him, and every craggy rock and river-stream, and blasts of winds shrill-piping stormy-breathed, and birds that dart through air on rushing wings. yet I endured mine heavy sorrow: Gods ought not with anguished grief to vex their souls. Therefore make end of sorrow-stricken wail for thy brave child; for to the sons of earth minstrels shall chant his glory and his might, by mine and by my sisters' inspiration, unto the end of time. Let not thy soul be crushed by dark grief, nor do thou lament like those frail mortal women. Know'st thou not that round all men which dwell upon the earth hovereth irresistible deadly Aisa (Fate), who recks not even of the Gods? Such power she only hath for heritage. Yea, she soon shall destroy gold-wealthy Priamos' town, and Trojans many and Argives doom to death, whomso she will. No God can stay her hand.' So in her wisdom spake Kalliope. - Quintus Smyrnaeus, Fall of Troy 3 631.

A week or two after Ivan's death on March 14, one of the landscapers, Sergio, noticed that I was not working alongside him and the others with my accustomed vigor and enthusiasm. Lacking the Spanish to convey my grief, I pantomimed wiping a tear from under my eye. Sergio peered at me for a few moments, then said, "Ivan die...Sergio die...Barbara die...everybody die." Then he shrugged his shoulders, smiled, and removed a weed from among the red petunias. I pulled on my garden gloves and went to work. BK