The Grapevine Art & Soul Salon

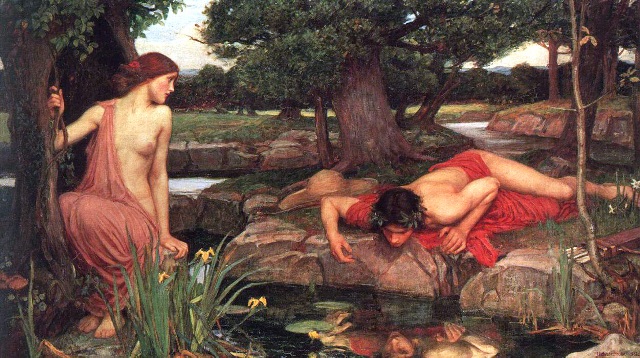

Is Narcissus the patron saint of imagination? His love was wholly given to and fulfilled by the reflected image that took him to the underworld.

James Hillman, The Dream and the Underworld (New York: Harper Collins Publishers, 1979, p. 119)

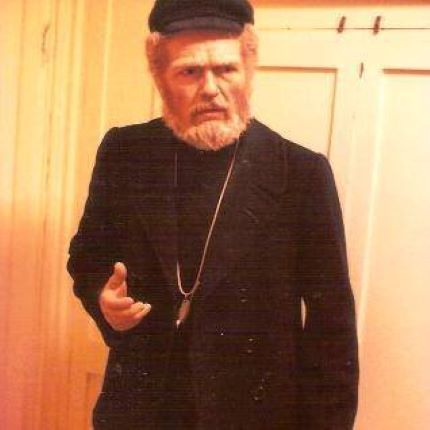

REFLECTIONS: Charles Knott, Host

Chamber for personal reflections, enough for a lifetime.

Hold to your own truth

at the center of the image

you were born with.

LOOKING INTO HILLMAN'S STUDY OF CHARACTER

In my previous article for this column I wrote the following:

Presently, I find myself wanting to learn the meaning of aging. Hillman's book, The Force of Character and the Lasting Life, written toward the end of his own life, is enlightening to an extraordinary degree. To help myself learn new things about aging, I would like to express to readers what I am learning from reading this book. But, first of all, this caveat: the book is a continuous stream of ideas, and no summary by me will come near being a substitute for reading the book, nor is meant to be. I am writing about this book so that I can understand it and so that I can present it and recommend it to you: James Hillman, The Force of Character and the Lasting Life, (New York: Random House,1999).

I followed these introductory remarks with a summary of Hillman's discussion of death as not the purpose of life or the purpose of old age. I also wrote about the biology of ideas, giving examples of instinctual ideas that are embedded in the body organs. In Issue 23, I would like to write about characterological changes that accompany the last phase of life.

Hillman succinctly and eloquently summarizes my own hopes for my advanced years when he says that they should be spent "for reviewing life and making amends, for cosmological speculation and confabulation of memories into stories, for sensory enjoyment of the world's images, and for connections with apparitions and ancestors." In his discussion of decrepitude (which, thankfully, is not yet upon me) he says that rather than attributing decrepitude to old age and the individual, we should look at our culture "and begin with the rigor mortis of its skeptical and analytical philosophies and the loneliness and dementia of its imagination." (p. 17)

One can make the argument that our character, good, bad and/or eccentric, reflects our world. After all, our society is inundated with its own negative qualities: the profit motive, sociopathic business models, shallow materialism, exploitation of the weak and vulnerable, neglect of the sick and homeless, wars of conquest. The list goes on and on. Somehow, it is up to us to form good character in ourselves in the midst of an educational system that encourages success in a world that is often shamefully wrongheaded. One could argue even that whoever would achieve good character must escape the predominant mold of our society. And it is in the nature of character itself to be molded, although I also believe we are born with character predispositions and destinies.

As I become more aware of my own aging, I find I am becoming more conversational with strangers, often saying things that are a bit outrageous. If I'm reading their reactions correctly, people enjoy a whimsical old man who is not shy about removing the filter that maintains a purely conventional surface in such greetings as: "Hello!" "Nice day we're having!" "Glad the rain finally left?" Nowadays I'm more likely to say, "Have you noticed that the Publix deli never cooks anything but fried chicken and mac & cheese? Yesterday, they had three different flavors of mac & cheese! What's wrong with these people?" Or, "I just can't get used to wine being kept in a box instead of a bottle! How do you feel about it?"

On the negative side, I spend a lot of time mumbling hateful things, looking with suspicion and contempt at things I don't approve of morally, while excusing, of course, some of those same things (and worse - sometimes much worse!) that I have done myself in my youth and may do again presently if the opportunity arises. I have always had my share of this character trait, but it seems that the older I get the more vehement are my emotions and the more likely I am to express them - consequences be damned! Of course, I am not reckless, just not so guarded, carefully walking the line between outright challenge and playful, frequently ironic provocation.

Archetypally, I am coming under the influence of the god Saturn in his negative aspect. To refresh the reader's memory, Saturn is one of the Titans who survives the coup in Heaven. He has many valuable positive qualities, but he is also portrayed as eating children! This is symbolic of his destruction through time of one generation after another of human life. When the archetype of his negative form takes me over, as would seem to happen often with elders, I become lethargic, neglectful of my duties, judgmental and harsh towards others, inclined to see ugliness, forgetful that I am of the same creation as that which I despise as well as that which I love. This ugly mood becomes a type of psychological self-indulgence which I think of metaphorically as compulsively sucking on a sore tooth.

This is the negative aspect of a new spontaneity I feel in striking up conversations with strangers. I heedlessly put on display personal eccentricities I concealed when I was young. Oftentimes the spontaneities are innocent, charming (I hope), and bring delight to friends and strangers. This spontaneity also has a risky side to it. When I see something I don't like, I really don't like it! Robinson Jeffers writes from what seems now a more familiar emotion, "I'd sooner kill a man, except for the penalties, than a hawk." I hasten to refer to a statement in a monologue by standup comedian Chris Rock: "I'm not saying I'd DO it, but I understand!" A pair of hawks periodically visit my front yard to remind me of that.

Back to the topic of the other mood: my new, good-humored sociability. I have also to deal with the fact that my sleep is troubled. I toss and turn and regret past transgressions. I ask myself how I could have been so stupid, so inconsiderate, so clumsy, so utterly unaware, and how I will go forward, knowing there is absolutely nothing to be done, because all the principals are long gone in memory, unnamed, scattered far and wide across the globe and, for that matter, many of them are in the ground.

Interestingly, in Plato's Republic, Cephalus, in conversation with Socrates, refers to the complaints of the old as "the doleful litany of all the miseries for which they blame old age" and adds, "There is just one cause, Socrates - not old age, but the character of the man." Cicero said, "Old men are morose, troubled, fretful and hard to please" and adds "some of them are misers, too. However these are faults of character, not of age." (as quoted in Hillman, p. 18). Faults of character, not of age. So, I can't blame aging for my crankiness and ill temper, nor can I credit old age for my sociability. These traits were in my character all along; it's just that aging has released them on to the world.

There is yet another possible cause for the negative fuming and fussing, the self-recriminations, the unwanted reminiscences. The purpose may be to empty out the heaviness of the old heart. Hillman reminds us that "Ancient Egyptian texts describing the preparation for life beyond show images of the heart as a scale balanced against a feather." He goes on, "In bed at night, or at the water's edge, we are filtering the residues accumulated by more than 3 billion heartbeats." (p. 124) And again, "Your image, encrusted with history, frees itself from that history; your native being is restored not to harmless innocence or bland amnesia, but to the essential lines of your bruised and faulty structure, you as you are, unable to be otherwise. Your character."

Taking our cue from the Egyptians: at the time of our deaths, the heart should be so light that it can be balanced against a feather. Old folks' mumbling and grumbling may well be outward signs of their final task: the lightening of the heart in preparation for leaving this world behind.

James Hillman'sThe Force of Character and the Lasting Life is, in my opinion, essential reading for those of us in the second half of life. Please give it a read.

Copyright 2020, Barbara Knott. All Rights Reserved.