Presentations: Nancy Law and Barbara Knott

Aragon Mill Village: Fiction and Photos

Text by Barbara Knott, photos by Nancy Law

Nancy Law's 2007 photographs of Aragon Mill Village follow two excerpts from Barbara Knott's fictionalized account of the village (called Muscadine), the mill, and their mother's work in it. Aragon Mill village actually was established by entrepreneurs from New York who called the railroad depot settlement nearby "Little New York."

"Aragon Mill" song written by Si Kahn, recorded by Red Clay Ramblers, and used with their permission.

1900

Settling the Village

Muscadine, Georgia, was conceived in New York City when William Redwine, entrepreneur, spoke to his brother Rudolph about the separation of cotton growers in the South from clothmakers in New England. "We're neglecting a great potential for enterprise. It would be much more efficient to take the mills to the cotton," he said. He was not the first to have the insight, but he was among the first to act on it. Looking for the right conjunction of resources for his project, he traveled by train through the Carolinas, where some of the first Southern mills were already up and running, and into Georgia.

Billy Redwine got off the train sixty miles northwest of Atlanta when he noticed the brick factory. In the town called Blackrock he took a room in Beulah's Boarding House, asking Beulah herself about the lay of the land.

On the other side of Hart Mountain, she said, there's a stretch of woods and a few farms that grow cotton. There is even a cotton gin, she said. How could he get there? Take the train like you was going to Rome, she said, and as soon as you get past the mountain, get it to stop and let you off.

He did, and the conductor pointed him toward Sudderth's Gin. He walked the two miles along a wagon path beside a field of cotton plants that had been picked nearly clean. Here and there, the sharp points of dry bolls had snagged a few white drifts of fiber.

It was late in the day on a Friday in September. The huge shed that housed the cotton gin was surrounded by wagons full of seedy lint brought in by farmers to be weighed and sold to Mr. Sudderth who would use his machine to process the cotton and then, by rail, send the seedless fiber twenty miles away to Rome. From there it would be transported to mills in the North.

Mr. Redwine considered the resources for building a local mill. There were sawmills on Hart Mountain to furnish building materials. There was not only the brick factory in Blackrock, there was even a cement plant. In addition to a ready source of cotton and a gin, he needed water to power the mill machinery. With Albert Sudderth's help, he located a place on Panther Creek where a dam could be built to create a millrace, an elevated canal or sluice, to run one or two water wheels. Finally, there was a railway for shipping the cotton cloth to markets. This, he decided, was where he would build.

The factory in Blackrock worked at top speed to supply bricks for a mill three miles north of the town. Beside the mill, within a year, the necessary trading site was established. It included a long, narrow, two-storied building made of wood: the company store, where millhands could purchase coffee, sugar and spices, as well as pots and pans, cloth, shoes and hats, and garden supplies. Next to it, there was a lowslung, wide building that housed the post office and barber shop. Brick facades on these two buildings identified them as belonging to the mill. Mr. Redwine was not long in finding all the laborers he needed and creating a grid of seven short streets with small clapboard houses for the millhands to live in.

Sudderth and Redwine conversed about what to name the village. Redwine wanted to give it his family name, but Sudderth discouraged that. His rejection followed some logic. Sudderth was aware that the reference to wine went against local sentiment toward the subject of drink: this was the publicly temperate South, and Redwine, even though a family name, was not appropriate for the mill or the village. Sudderth suggested instead a name to be taken from the condiment that, on the day they collaborated in naming the village, rested on the table between himself and Billy Redwine: muscadine, a local wild grape from which housewives were used to making jelly to sweeten their buttered biscuits. Mr. Sudderth offered Mr. Redwine one such biscuit to go with his morning coffee. Redwine agreed that Muscadine was a happy choice.

The villagers cooperated with the mill owners in constructing two houses of worship, a Baptist church beside the mill and a Methodist church on a high rise of ground beyond the village. A brick school building completed the ground plan of the new settlement. The main streets of the village all ended at the schoolhouse. On the other side of the schoolyard was the road that led to Blackrock in one direction and, in the other, to Rome. Across the road from the school, the Methodist Church faced a tract of land donated by Albert Sudderth as a burial ground.

Mr. Redwine's cotton mill represented a system of patronage that was attractive to people discouraged with the problems of sawmilling and farming, people who wanted dependable work. Everything they thought they needed was furnished for them by their benefactor at the mill where women and girls learned carding, spinning, and winding and where men mastered the skills needed to run the weaving machines and the machine repair shop. Early in the century the Redwine brothers brought the magic of electricity to the settlement, throwing the main switch one evening to light up the whole village at once. Those who were there never forgot the moment. At once the naked light bulb became a fixture in village homes, while the many dwellings outside the village continued to suffer the smoky emanations of the kerosene lamp.

Although eventually, during the restless '30's, such patronage systems gave rise to unions and strikes and negotiations in milltowns throughout the South, the union's impact on Muscadine was late and small and came only after Redwine had sold the mill. In the early days, he brought community to isolated rural people in this particular location among the foothills of the Great Smoky Mountains.

1928

Bernice McCarthy

One morning Bernice left her house and, instead of going to school, she stepped along behind her mother to the mill. That was in l925, when Bernice was l3.

The inside of the mill often appeared splendid at first to those who had chopped weeds from the hard rows of young cotton plants raised in the valley of Panther Creek below Hart Mountain and who had later picked cotton from the inhospitable bolls of mature plants and weighed it and sighed at how little wage came from so much work. Many people left the fields to run the mill machinery that might take off a hand if you weren't careful, but at least it wouldn't, like the cotton bolls, prick your fingers every working day for the rest of your life.

Bernice marveled at what she saw inside the brick building: vast rooms, polished hardwood floors, and, above all, powerful machinery that could outproduce any human who'd ever lived, and in all kinds of weather, too. She walked from one room to another, her eyes taking in everything from the bales of clean cotton that had been flattened out like quilt batting and then folded back and forth in neat stacks, to the pretty webbing that came off the carding machines in a V shape and got twisted into slivers: loose ropes of cotton that coiled in barrels until they rose over the barrel tops, white and light and lovely to look at. Then she watched the roving frame turn the slivers into yarn, and she followed the bobbins of loose yarn to the room where the thread was spun even tighter, swelling up spools that were conveyed onward to the weaving room where men operated the machines that made the cloth.

She stood beside her mother who worked a spinning frame, tying threads as they broke and replacing empty bobbins with full ones. The job was to keep the machine going. The task required nimble fingers and patience.

"I reckon I could do that," Bernice told her mother.

Eva was not so sure. At home, she often shooed her daughter away from the quilting frame when her stitches went every which way.

Despite her mother's misgivings, Bernice followed the pattern of most girls who lived near the mill. She thoughtlessly placed herself in service to a system that would keep her from ever getting what she eventually referred to as a "sitting-down job."

Three years later, she had lost the freshness of her first view of the inside workings of the mill. She had got used to the heat and the lint and the long hours standing, but the noise still hurt her ears. She couldn't think of anything to compare it to except maybe the sound of the train slowing down at Pine Station to drop off the mail or speeding up to leave the depot. The grating and whooshing of train wheels would make her put her hands over her ears until the noise subsided to a steady rhythm of rolling and clicking that was not so hard to bear and was sometimes even pleasurable. There was a difference in the comparison. The train came and left in a hurry, but the roar inside the mill stopped only when the machinery was shut down on Saturday afternoons and Sundays.

On a day in July 1928, Bernice's eyes moved back and forth over the whirring wooden cylinders, the upper ones thinning out while the lower ones swelled with thread. She walked up and down the aisles between machines. She stretched, leaned, pulled and tied thread, and walked some more. Her black hair was bobbed, a style that suited her, as did the bangs that fell neatly on her forehead. Under her work apron she wore a thin white sleeveless cotton dress printed with blue cornflowers. Balls of lint stirred by her feet floated above the varnished floor. She squeezed her toes together inside her work shoes where the leather had rubbed blisters.

Bernice wanted to catch Rosie Hancock's attention, but Rosie had her back turned. Rosie's long straight brown hair was parted on one side and woven into a plait that hung down to her waist. Bernice and Rosie were both l6. Sweat soaked through their cotton underwear and thin dresses. Barrelshaped Mr. Bowman, the fixer, came to check on their machines more often than he needed to.

"Check mine out while I take a little break," Bernice said. He grinned and wrinkled his eyebrows so that one tilted comically below the other. He puttered around Bernice's spinning frame while she moved to the side and sat down on a bench.

Before long, Rosie joined her and gave her a piece of chewing gum. They couldn't talk for the noise, so they used sign language that meant Watch out for Old Bowman's hands. Don't let him try to fix you now, hear? and Do you reckon Mr. Butts is going to pay us a visit today? Mr. Butts was the mill superintendent whose name they giggled at time and again.

A door opened from the next room. The girls heard underneath the roar of their spinning frames the faint rhythmic sound of the weaving machine: Shh shh shu shh. Shh, shh, shu shh. They stood up and moved toward their work stations. The door closed again. They stopped and mouthed some words about the weekend. Every Saturday evening at Rosie's house, her father and two brothers brought out guitar, banjo and fiddle to provide dancing music. Bernice tapped her feet to show how she looked forward to cutting the rug, as they called it.

The girls returned to their machines. Mr. Bowman took out his damp handkerchief, wiped the sweat from his eyebrows and picked up his bag of tools. Bernice nodded a thank you. When he was gone, Rosie Hancock rolled her eyes at Bernice who removed a full spool of thread, replacing it with an empty one, and began once more to patrol her machine.

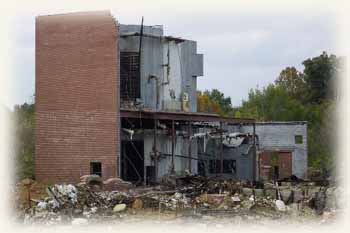

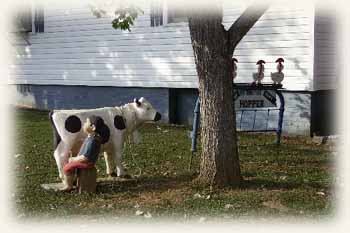

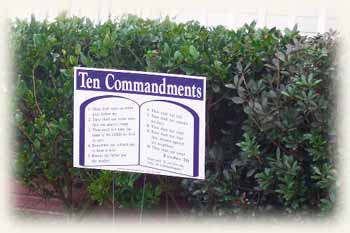

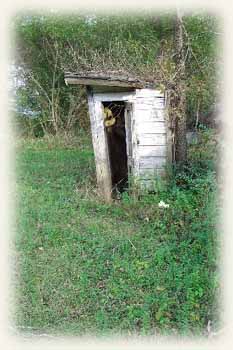

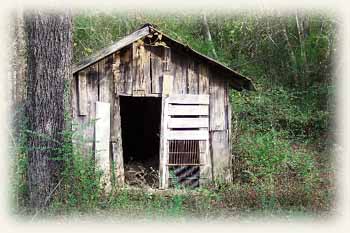

Photos of Aragon Mill Today